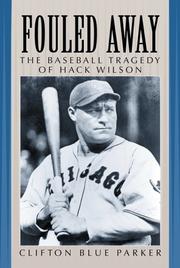

Fouled Away

By Clifton Blue Parker

Subjects: Biography, Baseball players, Baseball, biography

Description: Written By Bernie Weisz/Historian March 12, 2010 Pembroke pines, Florida e mail address: [email protected] title of review:"A size 6 Shoe, Size 18 neck, Blacksmith Arms: A "Sawed-Off babe Ruth" who Extinguished himself With his Own Talent. Tiny Feet, an 18" collar and size 6 shoes juxtaposed with a barrel-chest, blacksmith arms and tree truck thighs and short legs. At 5'6" and weighing 195 pounds, he was a physical oddity that prompted Baseball Hall of Fame historian Lee Allen to view Lewis Robert Wilson, the subject of Clifton B. Parker's biography "Fouled Away" as follows: "There was something comic about Hack Wilson. He looked like a sawed-off Babe Ruth. He took a lot of ribbing from opposing bench jockeys, and writers called him the "Pudgy One", but there was no denying his talent and fans took to him immediately". Parker's book is filled with tragedy, showing how Hack Wilson, a man of alcoholic extremes and described by sportswriter Thomas Holmes as: "perhaps the most malicious mauler known to baseball science, the most incorrigible exponent of brute strength verses a pitched ball" could hit rock bottom nearly one year after winning Major League Baseball's Most Valuable Player Award. There are photos interlaced within this tragedy that can make the strongest of hearted cry. Wilson's only son and sole carrier of his bloodline, Robert Wilson, is shown with Hack throughout the book, the victim of a bitter divorce between Hack and his first wife, Virginia Riddleburger. The reader can see the love and pride Hack had in these photos for his only son and love of his life. When Hack died on November 23, 1948 in a Baltimore, MD. hospital with what the death certificate read as "internal hemorrhaging, pulmonary edema and cirrhosis of the liver", his body laid unclaimed for three days. When Robert was contacted about his father's death, his only response was "Am not responsible". Like picking up a book about Lou Gehrig, the reader knows automatically that this story could only have a tragic ending. However, unlike the former, how many baseball fans have heard of Hack Wilson? And how did this man, a product of the roaring twenties, with Prohibition, Al Capone and the eventual Stock Market crash get the moniker "Hack"? Clifton Parker points out that it was either Wilson's resemblance to former Cub Lawrence H. "Hack" Miller or from an old time wrestler named George Hackenschmidt. Regardless, the nickname stuck. Parker tells of how Hack's father, also named Robert Wilson went to Ellwood City, Pennsylvania as a laborer in 1898 to look for work in the steel mills. One night at the bars, Wilson met 15 year old Jennie Kaughn, and a relationship started, culminating in her pregnancy of Lewis Robert Wilson on April 26, 1900. However, tragedy was an undercurrent in Hack's life, and when he was 7, his mother died of a burst appendix. Eventually, Hack realized this strengths were not academic and quit school in the sixth grade and searched for jobs to provide for himself. After he had been working for awhile, he moved at age 17 into his own apartment and held different jobs such as a printer's apprentice, an ironworker in a locomotive factory, and then in a shipyard, amongst others. Hack's father found a new wife and they maintained a bond throughout adulthood. At age 21, Hack finally found his forte was baseball and joined the Blue Sox, a minor league professional team in Martinsburg, West Virginia. Unfortunately for Hack, in his first professional appearance as a catcher he broke his leg at a close play at the plate, and this caused Wilson to later resume his career as a center fielder. It was during this time while he was mending that he met Virginia Riddleburger, a friend of a nurse who he would later marry. In his first season, Hack played in only 30 games because of his injury. However, he hit .356 with 5 home runs and quickly jumped to 30 home runs in 84 games in 1922, his second year of professional ball. This earned Wilson a promotion to Portsmouth of the Virginia League and won the triple crown there, batting .388 with 18 home runs and 101 RBI's in 115 games. The New York Giants brought him up for the last three games of the season and he would stay a Giant until the Chicago Cubs got Hack in the 1925 postseason draft. It was supposedly a clerical error, where the Giants failed to exercise the option on Hack, and for the nominal fee of $5,000, Wilson became a Cub. In Chicago, Wilson, the cleanup hitter, came into his own. Starting in 1926, Wilson won three straight home run titles, hitting 21 home runs, batting .321 with 109 RBI's. In 1927 his numbers were 30 home runs, .318 batting average and 129 RBI's and 1928 with 31 round trippers, .313 batting average and 120 RBI's. In 1929, his statistics were an incredible 39 home runs, .345 average and 159 RBI's. however, his role as the "goat" in the 1929 World Series loss to Connie Mack's Philadelphia A's is most remembered. He lost two fly balls in one inning of game four, and the A's rallied from an 8-0 deficit to win the game and eventually capture the series. Clifton Parker wrote in depth of the 1930 season, Hack Wilson's personal best, and is considered by some the finest in baseball history. He hit an incredible 56 home runs, a National League Record not broken until 1998 by Mark McGuire and Sammy Sosa, and later by Barry Bonds. He also batted .356 and a record 190 RBI's. Clifton Parker explained it changed to 191 RBI's in 1999 when baseball historians discovered that an RBI was mistakenly credited to another Cub and righteously awarded to Hack. Wilson was rewarded with a $33,000 annual contract, second behind Rogers Hornsby's $40,000 and Babe Ruth's $80,000. However, the Cubs finished second, and owner William Wrigley, who besides blaming future New York Yankee manager Joe McCarthy for the 1929 World Series debacle, threatened him that his job was in jeopardy. McCarthy always shielded Wilson from public scrutiny and deflected attention away from Hack's number one addiction, i.e. alcohol. McCarthy resigned rather than be fired, and was replaced with Rogers Hornsby, a man totally at odds with Hack Wilson. After the 1930 season, Hack won the MVP, and Parker wrote an ominous note: "For one glorious year, even while forces were conspiring against him, Hack Wilson had shined in one of the most amazing seasons ever. As high as he rose to stardom, as large as this small man had become in the game, Hack Wilson would tumble as quickly and as far away, into the shadows of a shrinking life". In 1931, Baseball changed and Hack Wilson began his nadir from which he would never recover. Parker explained that organized baseball did the following: "First, they deadened the ball by making it with a thicker cover and raised the stitches, which helped the pitchers grip it better. Two, the NL adopted the AL's ground rule double policy, which meant that when a ball bounced into the seats the batter got a two-base hit instead of a four base hit. Three, the sacrifice fly was abolished for any runners advancing, including those who scored on the fly ball out, thus giving the batter an official bat. The sacrifice fly was not reestablished until 1954." When Wilson reported to spring training at Catalina Island, California, he was significantly overweight and completely out of shape. As player-manager, Rogers Hornsby, considered an unpopular and zealous disciplinarian, instituted each day a four hour lunchless practice, wrote up weight charts of all the players' poundages and enforced midnight curfews, all ominous signs for Wilson. Wilson's personality clashed with Hornsby, who would not allow smoking nor drinking in the clubhouse and felt that players should save their eyesight for baseball by not reading or going to the movies. Rogers Hornsby was annoyed by Hack Wilson's swinging for the fences style. He was a three time .400 hitter, and felt winning involved the hit and run, delayed steals, and controlled batter swings within a disciplined strike zone. Parker quotes Billy Herman's opinion of Hornsby as follows: "He was a very cold man. He would stare at you with the coldest eyes I ever saw. If you did something wrong, he'd jump all over you. He was a perfectionist and had a very low tolerance for mistakes." In 1931 Wilson's production shrank to a .261 batting average, 13 home runs and 61 RBI's. Aside from the tweaked "dead ball", the pressure of his contract and living up to his 1930 record and Hornsby's constant harassment, Wilson was quoted as saying: "I couldn't get hold of the ball. It wouldn't carry for me and I was missing more swings than usual." Following the 1931 season the Cubs dealt Wilson to the St. Louis Cardinals for 38 year old pitcher Burleigh Grimes. This trade occurred on December 10, 1931, nearly a year to the date that Wilson won the MVP award. Wilson had hit rock bottom and the Cardinals general manager, Branch Rickey tried to capitalize on it. Rickey offered Wilson a $7,500 contract, a 77 percent pay cut, and Hack refused to sign it. Rickey shipped Wilson off to the Brooklyn Dodgers before he even put on the Cardinals uniform. Wilson made somewhat of a comeback in 1932 for Brooklyn, hitting for a .297 batting average, 23 home runs and 123 RBI's, but that was his last productive year ever. Incidentally, Rogers Hornsby, Wilson's main detractor, was found in 1932 to have borrowed $11,000 from Cubs players to repay severe debt that he incurred on betting on horse racing, and was fired at the end of the season. Hack Wilson continued his heavy drinking, which is believed to be the culprit in his rapid demise. He had a mediocre 1933 season for Brooklyn, batting .267 with 9 home runs and 54 RBI's and a horrendous 1934 campaign with two teams. Playing most of 1934 for Brooklyn, Wilson had a .262 batting average, 6 home runs and 30 RBI's and in a late season trade to the Philadelphia Phillies, he hit .100 with no home runs and 3 RBI's. Only four years after posting one of baseball's greatest seasons ever, Hack Wilson's career in the major leagues was over. Wilson did try unsuccessful comebacks with Albany N. Y. in the International League in 1935 (.263 batting average, 3 home runs and 29 RBI's) and with Portland, Oregon in 1936, but he finally retired from baseball and went through what Parker called Hack's "Wandering Years". Hack Wilson went home to Martinsburg, West Virginia and instead of settling into domestic tranquility with his wife and son, he took up an adulterous relationship with Hazel Miller, a girl in her mid 20's who waitressed at a recreation and pool hall where Hack spent much of his time drinking. Virginia Wilson felt bitterly betrayed, and little 12 year old Bobby watched his parents argue violently. In her divorce suit, Virginia accused Hack of contracting a venereal disease, which Wilson never disputed, and on June 12, 1938, they were divorced. In the spring of 1940, Virginia Wilson died after a lapsing into a Phenobarbital induced coma. Bobby Wilson was devastated. Hack came back for the funeral of his ex wife, but spoke awkwardly with Bobby and was unable to connect. Hack felt uneasy because his son had rejected him for mistreating his mother. Hack and Hazel, a willing drinking partner and listener to his tales and whom he would later marry, moved all over the East Coast, with stops in McKeesport, Pennsylvania, Chicago (there, Hack tried his hand at his own ill-fated bar, called "Hack Wilson's Home Run Club", which failed) and finally wound up in Baltimore, MD. There, he worked in a defense plant during World War II. Wilson also did stints as a pool manager and grounds keeper for the city park board. Clifton Parker included the story of Pat Malone, Wilson's best friend in baseball who traveled from Altoona, Pennsylvania to visit Hack one day in 1943. They drank together for two straight days, and then Malone took the train back to Altoona. Upon his return, Malone had to walk all the way home in a terrific rainstorm. Quickly contracting pneumonia, Malone died ten days later, at the age of 41. With continued drinking bouts, Hack began having blackouts and falls. Hazel had a mental breakdown, and her family came and took her back to Martinsburg. Alone now, Wilson's health took a serious turn for the worse. Soon after Hazel was taken away, Hack went to New York and appeared on a CBS talk show called "We The People". On that show, he used himself as an example of the evils of alcohol on radio. Hack's message was as follows: "I was at the top of my career. It happened in 1930. That was the year I won the MVP award. I received a salary of $40,000. I started to drink heavily, I argued with my manager and the rest of the players. I began to spend the winter in taprooms. When spring training rolled around, I was 20 pounds overweight. I couldn't stop drinking. I couldn't hit. That year most experts figured I'd break Ruth's record. But I ended up only hitting only 13 home runs. I was suspended before the season was over. I drank more than ever. I got booted from one minor league club to another, I worked odd jobs. I spent all my money, most of it in barrooms. Finally, I got sick. While I was recuperating in that hospital, I had a lot of time to think. There are kids, in and out of baseball, who think because they have talent they have the world by the tail. It isn't so. In life, you need things like good advice and common sense. Kids, don't be too big to take advice. Be considerate of others. That's the only way to live". One week after this interview, Wilson suffered another fall in his apartment and was brought by a friend to Baltimore City Hospital, where he died on November 23, 1948. It was Charlie Grimm, the Cubs Manager, who had the text of "Hack's Last Warning" on the CBS radio interview hung in the Cubs locker room at Wrigley Field. It is still there today. There are many other interesting stories that Clifton Parker included in this book. There are lessons of Chicago in the late 1920's and 1930's, the era of Prohibition and the resultant speakeasy's that many Chicagoans (including Hack and his cronies) frequented, as well as the amazing and strange story of boxer, baseball player and accused murderer Art "the Great" Shires. It is also interesting to note that after Wilson died, his body laid unclaimed for three days, juxtaposed with the 80,000 people that came to view Babe Ruth's body lay in state in the lobby of Yankee Stadium. This book caused a variety of emotions, sadness, and frustration, and made me think how his career would have been if he could have had the help afforded to players nowadays with similar substance abuse problems. Surely, Hack Wilson was one of baseball's immortals.

Comments

You must log in to leave comments.